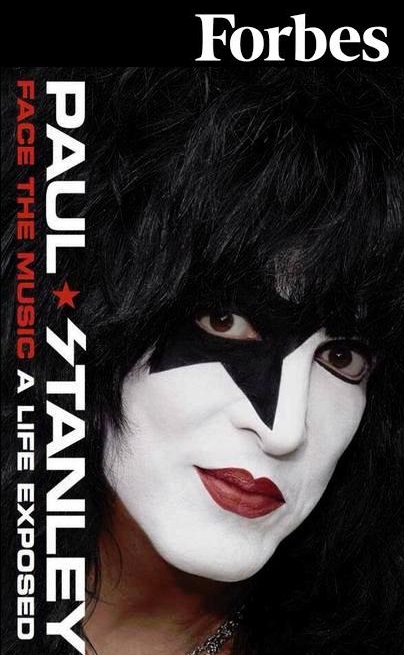

Book, Press

KISS’ Paul Stanley Overcame Deafness, Deformity And Bullying To Become A Rock Star

By Ruth Blatt

Growing up, Paul Stanley was an unlikely candidate to become a rock star. He was born with a facial deformity, microtia, which prevented his right ear from forming properly and left him deaf on the right side. Kids terrorized him, calling him “Stanley the one-eared monster.” He lived in constant fear: of being ostracized, or failing at school (because of his deafness), and of his mentally ill and sometimes violent older sister. His parents had their own problems and did not acknowledge or provide support for Stanley’s difficulties.

How did Stanley transcend this situation to become the front man of one of the world’s longest lasting and most successful bands, KISS? “We turn it around by incrementally succeeding,” he recently told me. “You don’t take giant steps. You initially take baby steps appropriately. As you have small successes and small wins, it encourages you to go the next step.”

In his new book, Face the Music: A Life Exposed, released on April 8 by HarperOne, Stanley goes through each of those baby steps, breaking down what appears to be an impossible achievement to its component parts.

His first small win was to get a spot in the choir for the glee club at his elementary school. Next was growing his hair over his ears, letting it frizz Hendrix-style. From then on, no one had to know he was any different. In fact, his looks became a selling point. In his first high-school band, he got a photographer to take pictures of the band. The pictures were so convincing that when an executive at CBS Records saw them, he called Stanley and said, “If you guys can play as good as you look, you’ll be great.” That was another small win for Stanley, even if no deal materialized from CBS.

Stanley’s intuition that overcoming his circumstances would be best achieved through small wins echoes the management wisdom expressed by University of Michigan psychologist Karl Weick in his classic paper, “Small wins.” Weick’s insight was that by emphasizing the severity of problems, we “disable the very resources of thought and action necessary to change them.” When you tackle problems in their full complexity, you end up feeling frustrated and overwhelmed. By recasting a seemingly insurmountable problem into smaller, more manageable ones, you gradually chip away at it by identifying opportunities to produce visible results.

Take the gay rights movement. In 1972, the Task Force on Gay Liberation succeeded in removing books on homosexuality from the Library of Congress’s “abnormal sex” classification, which also included books on sex crimes. That was a very small win, but an important step in the path toward expanding gay civil rights.

Harvard Business School professor Teresa Amabile and psychologist Steven Kramer, authors of The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work, empirically identified the power of small wins in people’s everyday work lives. They had 238 people who work on creative teams send them electronic “diaries” at the end of each workday. They were asked to describe events that stood out and fill out various questionnaires about their day. Based on almost 12,000 diary entries, Amabile and Kramer found that making small progress on meaningful work had the biggest impact on people’s inner work life experience.

Paul Stanley’s problems were big: deafness, deformity, bullying, unsupportive parents, unsympathetic teachers, a mentally ill sister, and no money. He tackled these through numerous small triumphs. It may seem counter-intuitive, but calling a problem small when you’re tempted to see it as insurmountable makes it easier to solve, especially if you don’t know what you’re doing.

When Stanley met band mate Gene Simmons, he knew it was a good idea to team up with him, despite their different personalities, because they shared the same work ethic, focus, and ambition. Finally he had a partner on his quest for stardom. They both understood, as Stanley writes on the book, that “Success wouldn’t happen by chance; it would happen by design.” And so they set about conquering the world, one small win at a time. They booked their own shows, at first playing to bewildered audiences of 35 people and gradually attracting bigger crowds. Ultimately KISS became one of the highest selling rock n’ roll acts of all time, with more than 100 million records sold worldwide.

In many ways, KISS’s career was a succession of small wins. They built up an enormous following show by show, fan by fan, not by making a killing on the sales charts or by getting extensive play on the radio. Though there were setbacks along the way, including albums that flopped, by focusing on the small wins KISS stayed resilient and kept moving forward.

“It’s certainly a lonely road when you plot your path and it goes against the grain or goes against the norm,” Stanley told me. “You have to rely on faith and passion. Passion will help you succeed. But passion will also help you deal with failure. I think that small victories keep us going forward and also near-victories keep us motivated to go forward.”